Check out the journal article about OSMnx. This is a summary of some of my recent research on making OpenStreetMap data analysis easy for urban planners. It was also published on the ACSP blog.

Check out the journal article about OSMnx. This is a summary of some of my recent research on making OpenStreetMap data analysis easy for urban planners. It was also published on the ACSP blog.

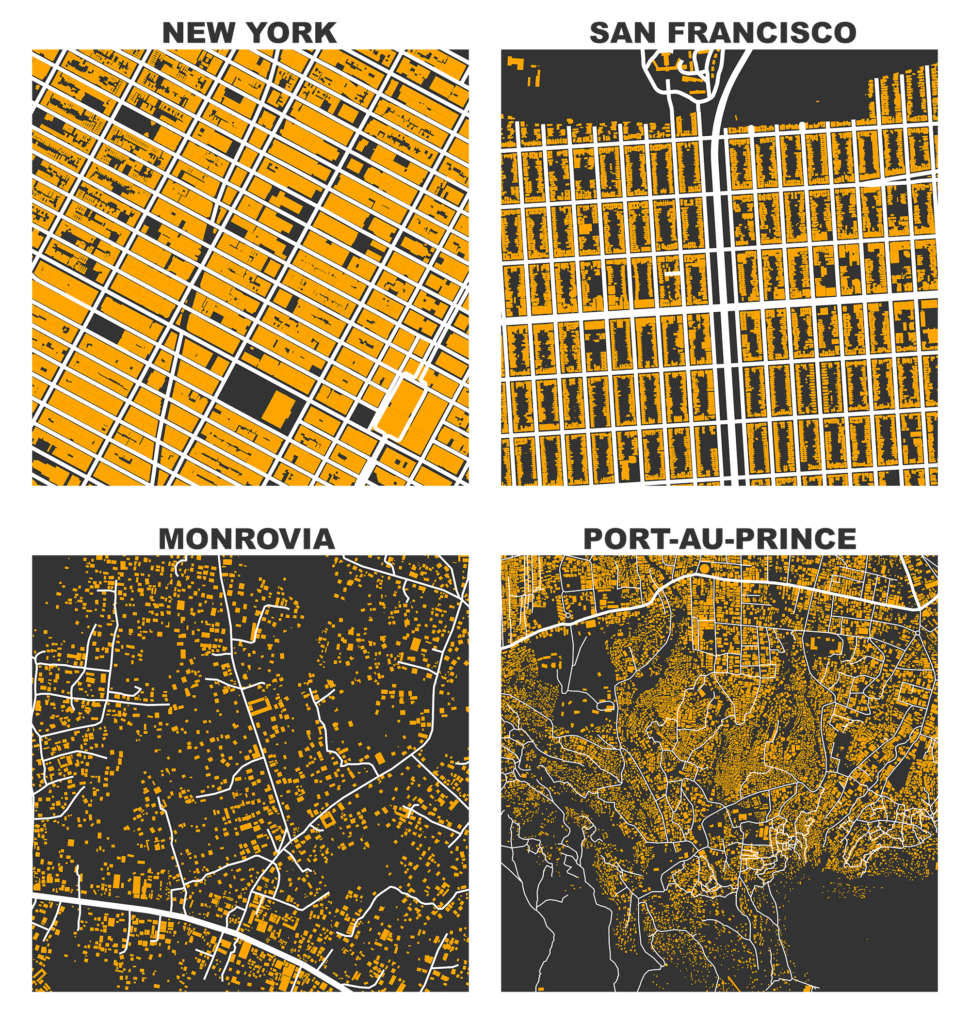

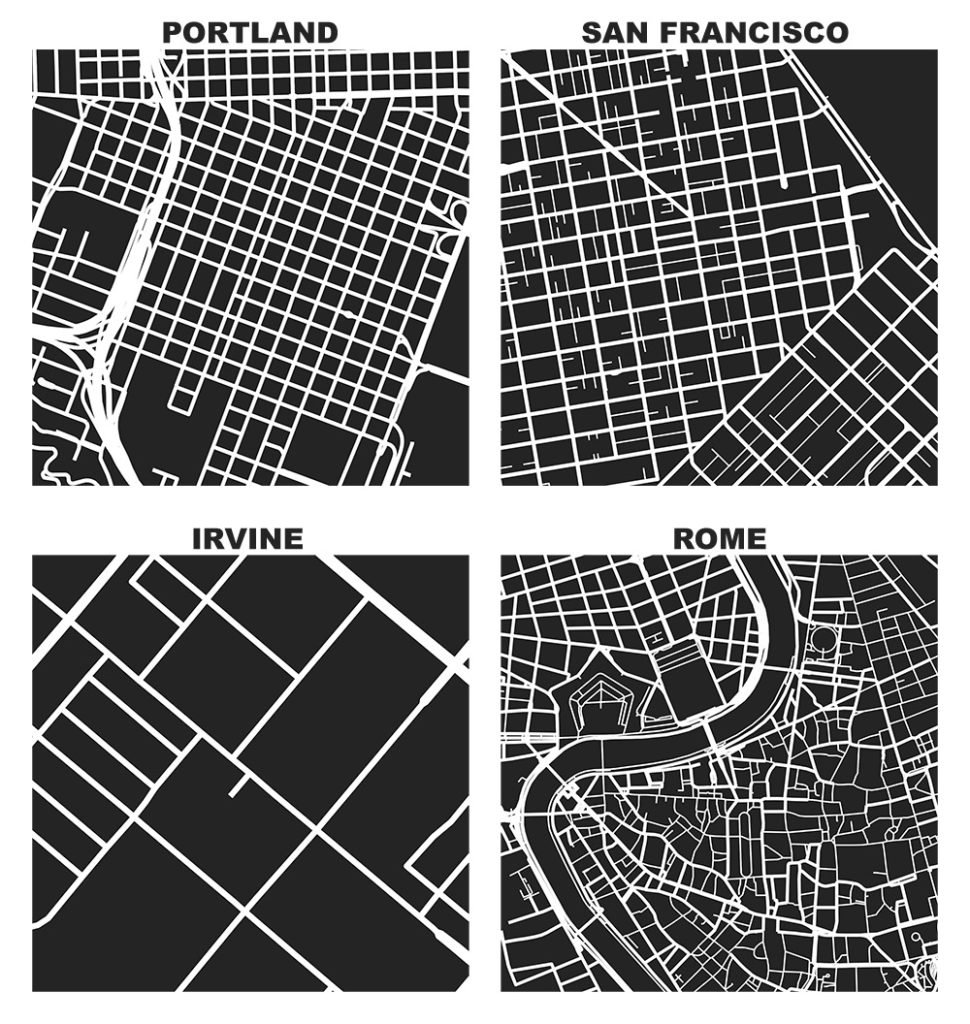

OpenStreetMap – a collaborative worldwide mapping project inspired by Wikipedia – has emerged in recent years as a major player both for mapping and acquiring urban spatial data. Though coverage varies somewhat worldwide, its data are of high quality and compare favorably to CIA World Factbook estimates and US Census TIGER/Line data. OpenStreetMap imported the TIGER/Line roads in 2007 and since then its community has made numerous corrections and improvements. In fact, many of these additions go beyond TIGER/Line’s scope, including for example passageways between buildings, footpaths through parks, bike routes, and detailed feature attributes such as finer-grained street classifiers, speed limits, etc.

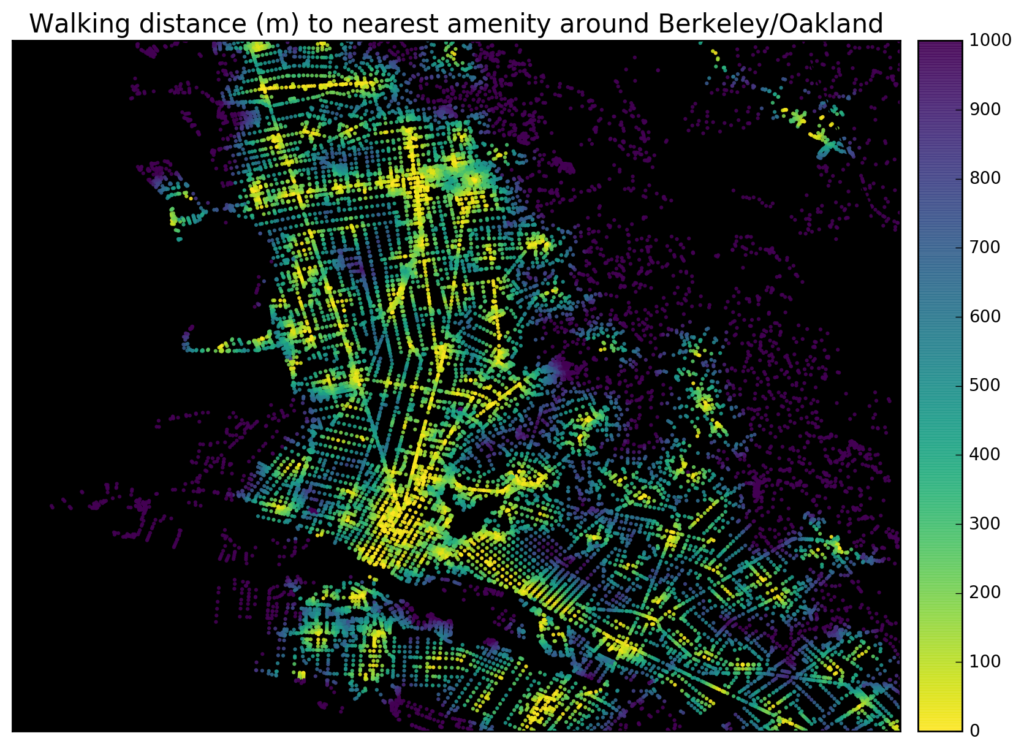

This presents a fantastic data source to help answer urban planning questions, but OpenStreetMap’s data has been somewhat difficult to work with due to its Byzantine query language and coarse-grained bulk extracts provided by third parties. As part of my dissertation, I developed a tool called OSMnx that allows researchers to download street networks and building footprints for any city name, address, or polygon in the world, then analyze and visualize them. OSMnx democratizes these data and methods to help technical and non-technical planners and researchers use OpenStreetMap data to study urban form, circulation networks, accessibility, and resilience.

This is a guide for absolute beginners to get started using Python. Since releasing

This is a guide for absolute beginners to get started using Python. Since releasing

If you use OSMnx in your work, please cite the

If you use OSMnx in your work, please cite the

Check out the

Check out the

A guide to setting up the Python scientific stack, well-suited for geospatial analysis, on a Raspberry Pi 3. The whole process takes just a few minutes.

A guide to setting up the Python scientific stack, well-suited for geospatial analysis, on a Raspberry Pi 3. The whole process takes just a few minutes.