Craft Beer, Urban Planning, and Gentrification

I co-authored a chapter in the new book Untapped: Exploring the Cultural Dimensions of Craft Beer with the estimable Jesus Barajas and Julie Wartell. Our chapter is titled “Neighborhood Change, One Pint at a Time” and it explores the relationship between craft breweries, urban planning and policy, and gentrification.

We found that many cities have changed their zoning codes recently (and even offer subsidies) to make it easier to establish craft breweries and brewpubs, with the goal of economic development. There’s a strong narrative (and anecdotal evidence) of craft breweries “revitalizing” neglected neighborhoods. New breweries often seek inexpensive industrial spaces in close proximity to urban centers and residential districts. In turn, they serve as anchor institutions that appeal to whiter, wealthier, and more educated demographic groups. Many craft brewers explicitly see themselves as agents of neighborhood revitalization and “committed urbanists.” The brewers we interviewed uniformly stated that neighborhood character was an important or even primary reason for their location choice, and many referred to themselves as pioneers and catalysts in neglected historic neighborhoods.

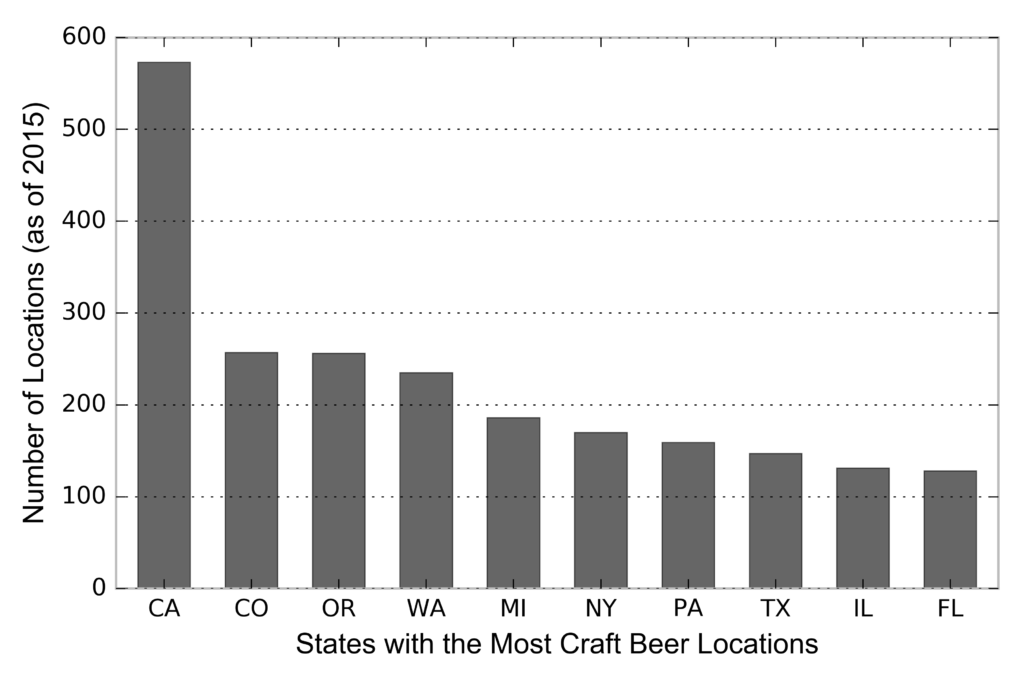

Do breweries instigate revitalization, gentrification, or displacement? To date, there hasn’t been clear evidence of the relationship (or even the causal direction, if any) between craft beer and neighborhood change. So, we used a geocoded, complete nationwide data set of craft brewery openings and closings from 2004 to 2015 to examine this relationship. These breweries concentrate in cities (over 90% of the census tracts with a craft brewery are in urbanized areas). The West has the most locations and the South has the fewest. In particular, California has by far the most craft beer locations (more than twice as many as the next closest state… it is, after all, the most populous state), followed by other western states:

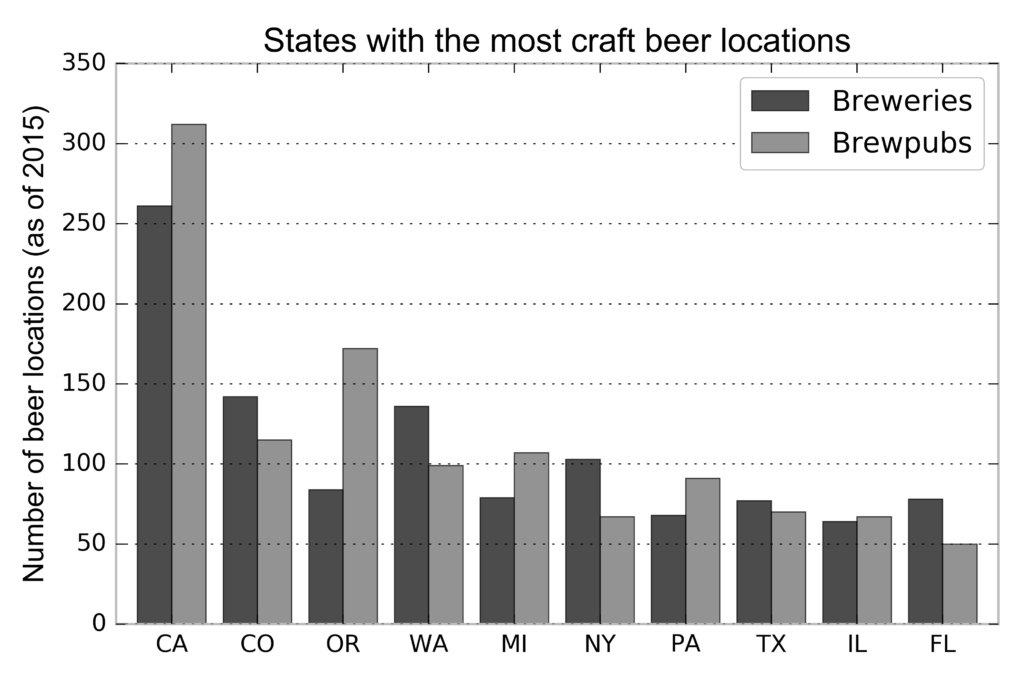

We can also break these locations out by type—that is, breweries versus brew pubs:

Neighborhoods with craft breweries tend to have densities equivalent to inner- ring suburbs. They also tend to have more white residents, a higher proportion of people aged 25–34 years, fewer households with children, more education, a slightly lower median income, a higher proportion of people in professional or technical occupations, more new housing, and higher housing prices.

We estimated a series of logistic regression models, which predict whether a census tract has a new craft brewery given a set of demographic and neighborhood change variables. We cannot conclude that new craft breweries cause changes in neighborhood indicators, but we can see how they follow them. Changes in racial composition do not seem to be a draw for new craft breweries, but increasing education levels, declining income levels, and an older housing stock do appear to draw craft breweries.

Displacement of longtime residents is a key challenge facing economic revitalization of disinvested neighborhoods. We advocate for urban planners to recognize the potential importance of craft breweries in neighborhood revitalization while also protecting residents from displacement. Read more in the chapter.